Shannon K. Winston reviews

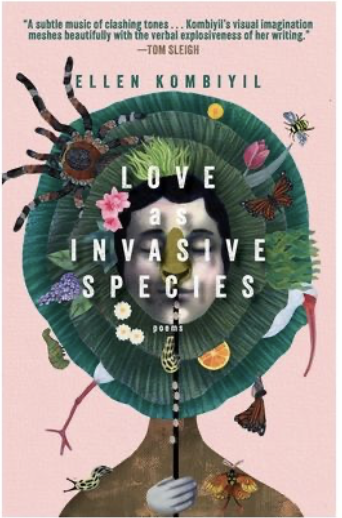

Love as Invasive Species

by Ellen Kombiyil

Love as an Invasive Species

by Ellen Kombiyil

Cornerstone Press

2024

Paperback, 100 pages

$21.95

Ellen Kombiyil’s Love as Invasive Species explores the capacity to love in the face of family trauma, inherited shame, and class struggle. The poems are simultaneously beautiful and caustic, tender and gut-wrenching. These tensions are foreshadowed in the collection’s title, which equates love with an “invasive species.” . In probing these paradoxes, Kombiyil’s hope is that “we continue to learn to love each other better” (xix). Formally innovative, this work was conceived as a “double book,” in which the first half is inverted and mirrored in the second half. Thus, the poems in “Side A” serve as nuanced companion pieces to “Side B.” For example, both opening poems are titled “Prayer” and directly address the speaker’s daughter—fitting, as daughters and gender are central themes in the collection. In one poem, the daughter is a newborn, someone the speaker is just getting to know and love; in the other, the daughter is an older child who is getting to know and love the world through science. Read side by side, these poems help understand the speaker’s wonder at her growing daughter. These poems, like the collection as a whole, possess a beautiful refractive quality; while each poem shines on its own, it gains greater poignancy when viewed through the lens of its companion piece.

The double-book structure allows Love as Invasive Species to complicate linear chronology: beginnings double as endings, while the black-page midpoint both divides and connects the halves. On Side B, there is also a chronology outlining major events in the poet’s family—including births, women’s struggles with postpartum depression, and deaths. These familial events are intertwined with national events, such as the 1988 update to the Fair Housing Act, and the 47th anniversary of Roe v. Wade. The personal is thus inherently political and vice versa. While Kombiyil’s takes on large social issues, she does so through a deft attention to everyday details and a fierce lyricism. “No Money for Boots,” for example, begins:

Ma wanted birthday lilies

so you stomped through snow

to the florist’s beige counter, tiled floor.

Tiger lilies. No dull

white for her, no pink tongue center

yanked fresh from a mountain path.

It was six years since Daddy

plucked the spark plugs and left (4).

Through particulars like the poem’s title and the mention of the father’s departure, the poem evokes poverty and heartbreak. Yet, vivid images—the snow, the florist’s counter, and the lilies that “yawned fresh from a mountain path”—also create a sense of tenderness, with the flowers symbolizing small acts of love. The poem’s alternate title, “Love as Uprooted Flora” (printed in light gray to the right of the page), explicitly frames the lilies as a gesture of love.

In addition to the flowers metaphor, Love as Invasive Species evokes flora, fauna, and other elements of nature to explore love’s many complexities. The collection raises fundamental questions, such as: What is love? How does one love? And, as the epigraph asks, “How do we learn, what are we taught?”—both about love and the world. In the title poem, love is presented as a tarantula that escapes from its cage. The poem traces the speaker’s search for the missing pet: “At night, I dreamt it crept// across the headboard as I slept, scuttled clacks, / each foot a seed-hard talon, spilled cracks” (11). Like love and the desire for love, the tarantula is elusive and hidden (at times in plain sight). The poem concludes:

The cage is empty—I bring home a mate

and watch it sleep under the heat lamp,

tap at the glass, hoping

I’ll find a way to live again

grateful, tame

among the rocks (12).

The speaker longs for the tarantula as one longs for love. In the final stanza, she identifies with it, imagining herself “among the rocks.” Love, here, is shaped by longing, imagination, and—through the use of the cage—entrapment.

Love as Invasive Species also explores love in relation to the body. In “Not About Sex,” for example, the speaker states: “I am trying not to think about sex/but I heard the French prefer breasts//that fit into champagne flutes” (15). The speaker reflects fashion trends and pressures on women to conform to a certain body type—whether lithe, as in the above lines, or “androgenous,” or “curvaceous” depending on the decade and fad (15). In the end, the poem offers an alternative to this pressure by returning to the speaker’s childhood memory. Decked out in snorkeling gear at the pool, she and her friend “could pretend/ for a time we were platypuses” (15). By turning to the animal realm, the poem subverts gender norms and delves into the playfulness of the imagination. If love signifies social pressure or entrapment in one poem, it embodies joy in another and agency—or its absence—elsewhere. Love also emerges as a celebration, as in “Hair” where the speaker compares hair to peaches: “if you put it near/your mouth” (32). The body, in this poem, is tender and sweet—something to be experienced through the senses.

Love as Invasive Species is a must-read: it raises urgent questions about how we love and care for one another, especially our daughters. These concerns feel especially pressing today. And just as love has no single point of departure or origin, neither does this collection. One can start with Side A and move to Side B or alternate between them. For those drawn to family narratives, the book captures these dynamics expertly. Characters like Ma, Aunt Blanche, the speaker’s sister, and even the speaker’s absent father are rendered so vividly through snippets of conversation and precise memories that the reader can’t help but feel as though she knows them. And for nature lovers, the luscious and complex invocation of plants and animals throughout Love as Invasive Species offers yet another point of entry. It is rare to encounter such a capacious, kaleidoscopic collection, which makes it a truly unique and marvelous read.

Shannon K. Winston is the author of The Worry Dolls (Glass Lyre Press, 2025) and The Girl Who Talked to Paintings (Glass Lyre Press, 2021). Her individual poems have appeared in Cider Press Review, Los Angeles Review, RHINO Poetry, and elsewhere. For more, find her here: https://shannonkwinston.com/.

Ellen Kombiyil is the author of Histories of the Future Perfect (2015), Avalanche Tunnel (2016), and Love as Invasive Species (2024). Recent work has appeared or is forthcoming in New Ohio Review, Nimrod, North American Review, and Ploughshares. A graduate of the University of Chicago and Hunter’s MFA program, she teaches at Hunter College.